Was discovered a material which becomes a superconductor at 15ºC, after more than a century of search.

Source: Science News

The discovery evokes daydreams of futuristic technologies that could reshape electronics and transportation. Superconductors transmit electricity without resistance, allowing current to flow without any energy loss. But all superconductors previously discovered must be cooled, many of them to very low temperatures, making them impractical for most uses.

To understand how superconductors work, clique in the following link.

Now, scientists have found the first superconductor that operates at room temperature — at least given a fairly chilly room. The material is superconducting below temperatures of about 15° Celsius (59° Fahrenheit), physicist Ranga Dias of the University of Rochester in New York and colleagues report October 14 in Nature.

However, as expected, the material only becomes a superconductor under extremely high pressure. What makes practical uses impossible.

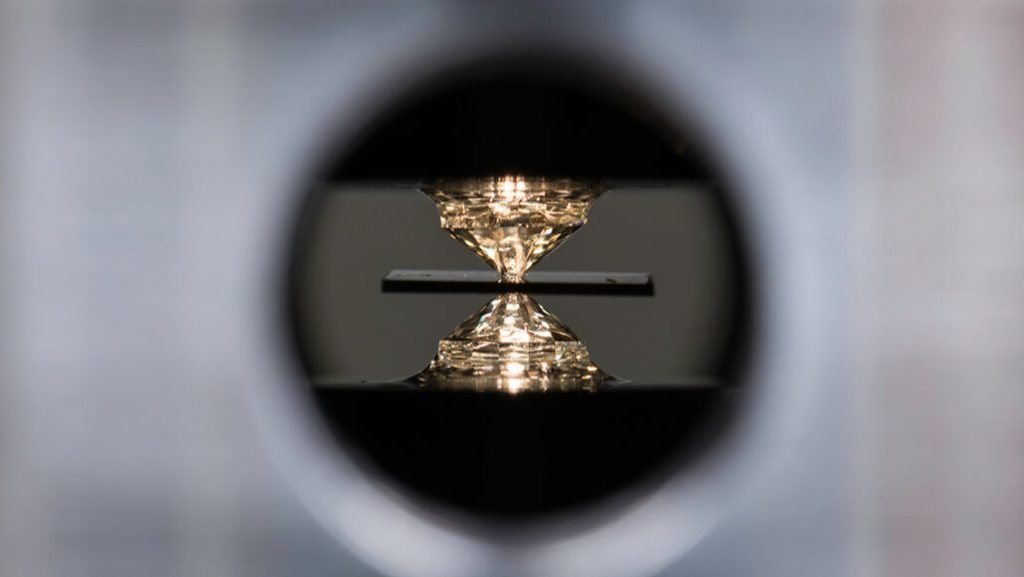

Dias and colleagues formed the superconductor by squeezing carbon, hydrogen and sulfur between the tips of two diamonds and hitting the material with laser light to induce chemical reactions. At a pressure about 2.6 million times that of Earth’s atmosphere, and temperatures below about 15° C, the electrical resistance vanished.

Superconductors and magnetic fields are known to clash — strong magnetic fields inhibit superconductivity. Sure enough, when the material was placed in a magnetic field, lower temperatures were needed to make it superconducting. The team also applied an oscillating magnetic field to the material, and showed that, when the material became a superconductor, it expelled that magnetic field from its interior, another sign of superconductivity.

The scientists were not able to determine the exact composition of the material or how its atoms are arranged, making it difficult to explain how it can be superconducting at such relatively high temperatures. Future work will focus on describing the material more completely, Dias says.

When superconductivity was discovered in 1911, it was found only at temperatures close to absolute zero (−273.15° C). But since then, researchers have steadily uncovered materials that superconduct at higher temperatures. In recent years, scientists have accelerated that progress by focusing on hydrogen-rich materials at high pressure.

In 2015, physicist Mikhail Eremets of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues squeezed hydrogen and sulfur to create a superconductor at temperatures up to −70° C (SN: 12/15/15). A few years later, two groups, one led by Eremets and another involving Hemley and physicist Maddury Somayazulu, studied a high-pressure compound of lanthanum and hydrogen. The two teams found evidence of superconductivity at even higher temperatures of −23° C and −13° C, respectively, and in some samples possibly as high as 7° C (SN: 9/10/18).

If a room-temperature superconductor could be used at atmospheric pressure, it could save vast amounts of energy lost to resistance in the electrical grid. And it could improve current technologies, from MRI machines to quantum computers to magnetically levitated trains. Dias envisions that humanity could become a “superconducting society.”

To next stage is to find a superconductor material to reasonable temperatures with the lowest pressure possible.